Everyone loves an extra income stream – even the super-wealthy owners of luxurious properties that they only inhabit for just a few weeks each year. Offering a property as a short-term rental through a platform like Airbnb can provide a wonderful side hustle. For some owners, however, the associated hassles could be a powerful deterrent to using the service. Text messages at 3 a.m. about Wi-Fi passwords, stopped-up toilets, and the lack of water pressure in the shower might be just enough to tip the scales against such an undertaking…especially when such messages are followed up by angry “Why isn’t this fixed yet?” queries just 30 minutes later.

So what if an all-in-one concierge service could take away ALL of those hassles? If an intermediary service could handle all of the tenant interactions, the marketing, the logistics of the key hand-offs, etc. then suddenly the idle rich jetsetters might be a bit more willing to open up their pied-a-terres to the unbathed masses. Such a service would benefit all stakeholders – travelers would have more options, the property owners would earn more income, and the platform would receive more commission fees from the extra transactions. In exchange for a fee paid to the service, willing property owners could have a side hustle that was “all side, no hustle.”

Let’s imagine that such a service is looking to establish itself, with an initial marketing outreach effort to high-end property owners not already using Airbnb. Let’s also imagine that this new service is operating on a shoestring budget, and therefore needs to. How can it identify the properties within a city that are most likely to command high values in the short-term rental market?

The Naïve Bayes classifier is a good candidate for the task at hand because of its simplicity, computational efficiency, and ability to handle categorical variables. Furthermore, its classification outcomes come with associated probability values – we can use those to identify records that are most likely to belong to some particular group. To illustrate how this method could be used to solve the business problem outlined above, I will utilize Airbnb data of San Francisco listings.

One of the first decisions the modeler must make is deciding how to bin the data. In this case, the question is which numerical variable would you use to separate the properties? Would you use price, review ratings, or number of reviews? Each of these variables has a different impact on the outcome and may not be equally effective at separating classes. If the classes are not well separated, then even a large dataset will not be helpful.

The next important decision is to determine the number of classification categories you would like to create. Also, what would the cut-off be for each group? In other words, should you create four groups and bin them equally? Or should you create three groups by dividing the data according to a 15-70-15 proportion, 20-40-20, or 30-40-30…etc? The decision made at this step has a big impact on the model.

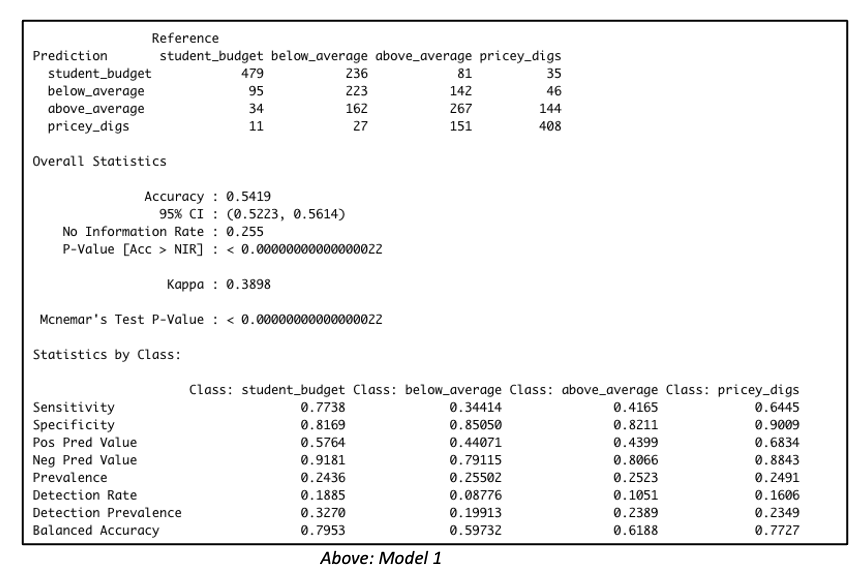

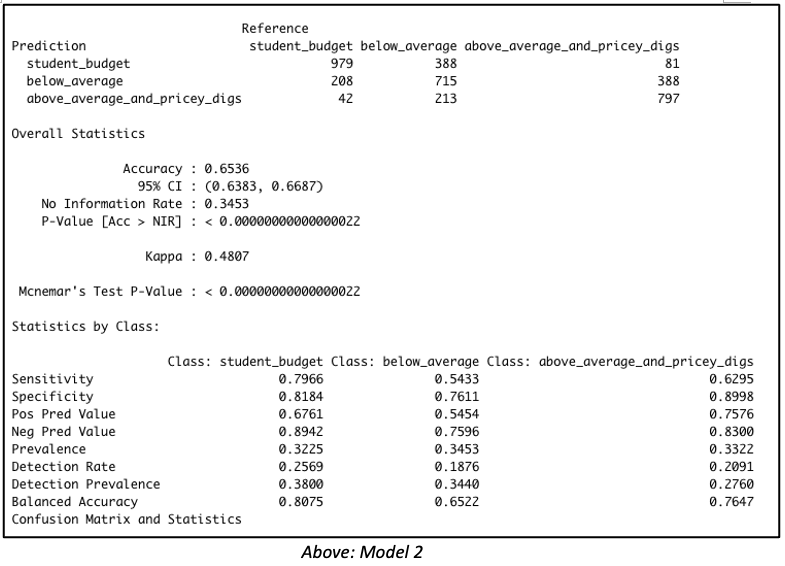

Consider both models below which were each created with 3811 rows of data representing 60% of the total dataset. Both models were created with the same predictor variables, such as the number of bedrooms, bathrooms, property type, location, etc. But in Model 1, the data was binned into 4 equal groups while in Model 2, the data was binned into 3 equal groups. The model summary for Model 1 showed the model has an accuracy of 54.19%, which is good considering that this performance is slightly more than double the No Information Rate (Naïve Rate). Model 2’s accuracy’s level is at 65.36%, a level which is nearly double its No Information Rate.

These are encouraging results but in our Airbnb example, we are more interested in knowing how well our model performs when it is asked to classify properties into any of the classes used in the model. For this reason, it is worth considering the true positive rate i.e. ‘sensitivity’. Model 1 is better at predicting the true positives (‘sensitivity’) for classes at opposite ends of the spectrum. This suggests Model 1 has difficulty reading nuances. On the other hand, Model 2’s performance in this regard is comparatively more balanced.

But wait – let’s get back to our original goal. While overall accuracy is good to see, what we are most interested in here is identifying that high-end price group. Owners of such units will be the best targets for our all-in-one concierge service. Therefore, let’s dive a bit deeper to examine this model’s suitability for identifying such properties.

By running the predict() function with the type=’raw’ parameter included, we can view the associated probabilities for each outcome class, and then rank records by probability of belonging to some particular outcome group.

Taking this approach with the validation set, we find that among the 100 records identified by the model as most likely to land in the top tier group, 96 truly belonged to “Above Average and Pricey Digs.” Among the 150 likeliest, 140 units, or 93.33%, actually belonged to that group, and among the 200 likeliest, 185 units, or 92.5%, were truly in that top tier.

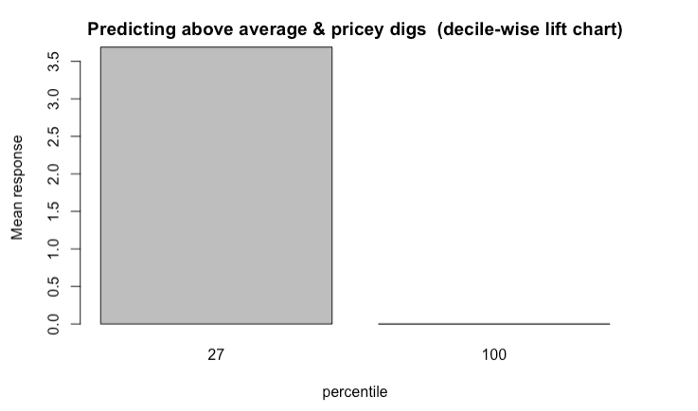

But that’s not all. It is worth going one step further by evaluating the model with lift charts or decile-wise lift charts because these charts determine how effectively our model ‘skims the cream’.

The decile-wise lift charts below illustrate how effectively the model can predict membership in the ‘above average and pricey digs’ group. When the model is used to classify the top 27% properties in this category, its performance is more than 3.5x better than a random guess.

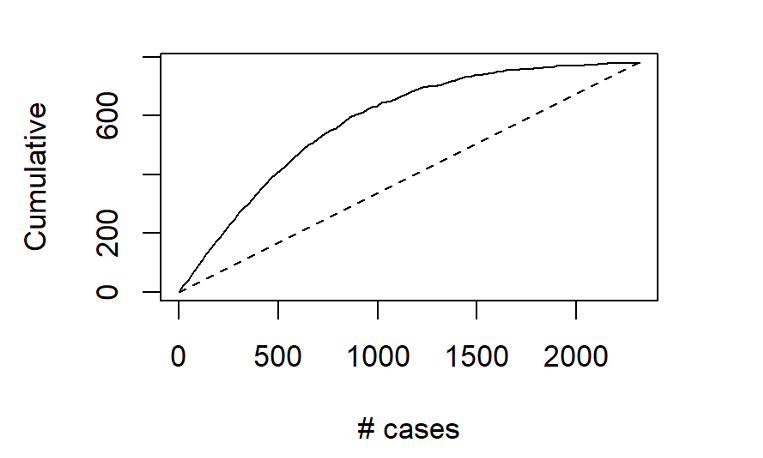

Another way to assess the model’s ability to identify top-tier rentals is with a two-dimensional lift chart. Such a chart only works with two-outcome class scenarios, so we start here by collapsing the first and second tiers together, and then labelling that group as “other.”

In the entire validation set, there are 780 units that land in the highest price tier. The values along the x-axis represent all the validation set records, ranked in order of their probability of belonging to the highest-tier class. The y-axis shows the number of correct predictions. The solid line represents the model’s performance – it shows us, for instance, that among the 500 records that the model says are most likely to land in the Above Average & Pricey Digs Tier, just over 400 truly did belong to that group. The line flattens out at around x=1500, because by that point, the model has already identified nearly all of the records that truly belonged to this outcome class.

The dotted line, by contrast, shows how effective a model would be if it simply labelled all the records as belonging to the top tier. Since 33.6%, of the validation records belong to this group, each x-axis value here corresponds to a y-axis value that is exactly 33.6% as large. The difference between the solid line and the dotted line represents the model’s improvement as the number of cases increases.

What do these results mean for the concierge service? Let’s revisit our original assumptions:

- such a service would most likely appeal to the owners of properties in the highest pricing tier;

- the initial outreach efforts should be made to owners of properties not already registered with Airbnb; and that

- the new service has a limited budget, and therefore needs to carefully focus its outreach efforts only on that tier of properties whose owners would be likeliest to use it

As demonstrated here, the model delivers quite effectively in this regard, especially when we maintain a relatively narrow focus on the properties that are most likely to be top tier. Splashy magazine inserts, Super Bowl advertisements, and big-ticket endorsements from celebrities might be in the cards for this service down the road, after it spreads across the globe and prepares for its IPO roadshow. For now, though, the hyper-specific focus that can come from “skimming the cream” off the top of those Naïve Bayes model probability predictions may be the surest next step for this service’s success.

Data source: Inside Airbnb